My paper on the Jerusalem papyrus has been translated and published by The Conversation Global and The Huffington Post.

Compared to the French version, it features minor revisions and can be cited thus: Michael Langlois, “How a 2,700-year-old piece of papyrus super-charged the debate over UNESCO and Jerusalem” in The Huffington Post, November 15, 2016.

You can directly read it here:

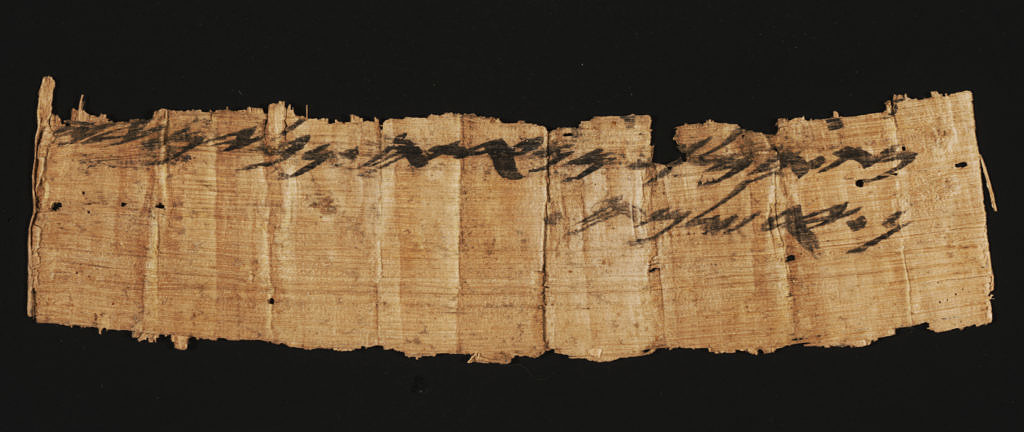

On October 26 2016, the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA) unveiled a 2,700-year-old papyrus that mentions the city of Jerusalem.

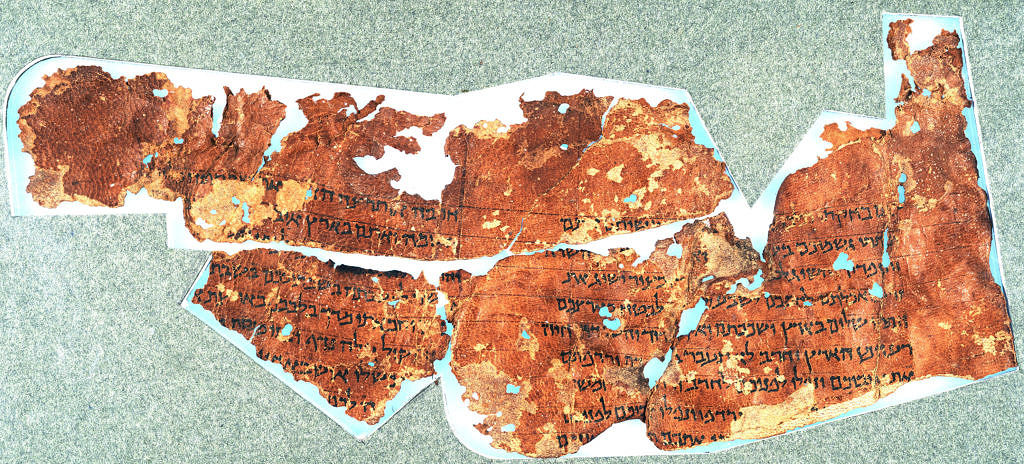

The papyrus was not found during official excavations so its origin is uncertain. It is said to come from one of the numerous caves in the Judaean Desert along the western shores of the Dead Sea. This is a suitable environment for the preservation of such fragile documents; nearly 1,000 ancient manuscripts copied on parchment or papyrus have been found in the area.

Most of them were discovered by local Bedouin people who know these caves better than anyone else and are fully aware of the value of these old fragments on the antiquities market. But this time, Israeli authorities heard that a new papyrus was for sale and launched an operation that led the confiscation of this precious item.

This is not a first for the IAA: they have been fiercely fighting against the trade in antiquities, sometimes to the point of wrongly accusing scientists of collaborating with counterfeiters in what has looked like a witch-hunt.

What does the papyrus say?

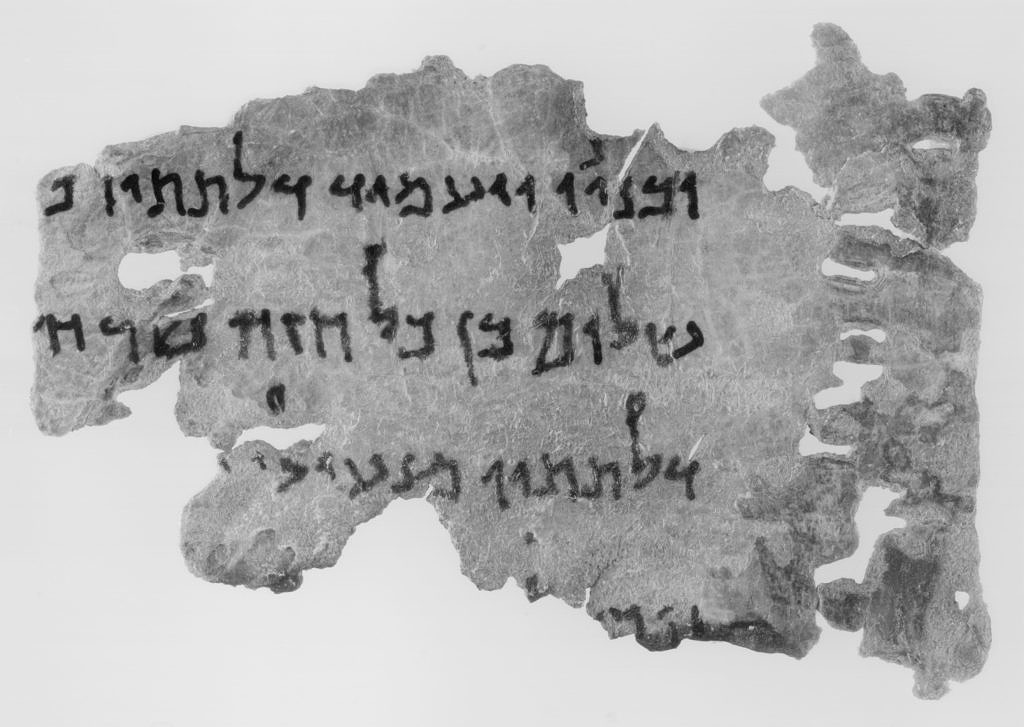

Only three lines of Hebrew script have been preserved on the papyrus strip, which measures 10.9cm × 3.2cm. The tearing on the top and bottom margins indicates that what we have here is the end of a document. I provisionally read the following text:

2′) נת.המלך.ממערתה.נבלים.יי3′) ן.ירשלמה.

Translated into English, it says:

2′) … the king, ‹coming› from his cave, two jars ‹containing› wi-

3′) ne, towards Jerusalem.

The few traces of letters at the top are insufficient to reconstruct the first line, even less those that precede it. The first two letters of the second line preserve the end of a word whose reconstruction is likewise uncertain. Then comes the mention of the king and of a term that my Israeli colleagues read as “from Naarata”.

I would rather translate it as “from To-Naarat” (as in the Bible, Joshua 10.36) but, on the photograph I saw, the first letter seems to be an M, so I provisionally propose to read “from his cave” or “from To-Maarat” until I can examine the fragment itself.

Maarat is a Judahite city mentioned in the Bible (Joshua 15.59), but the same term also means “cave”, so two translations are possible, the cave being then used as a wine cellar. The number of jars is uncertain: I propose to read “two jars” but one can also read “jars”.

Last but not least, the document ends with the mention of the jars’ destination: Jerusalem. It is this word that drew the attention of the media. We are told that it is the first time that the holy city is mentioned on such a papyrus.

The mention of Jerusalem

According to the IAA, radiocarbon dating puts this papyrus in the seventh century BCE. As a matter of fact, dating based on carbon-14 or on the shape of letters do not yield precise dates at that period. So this papyrus could be dated to the preceding century or the following centuries.

Though it is unusual for such a fragile document to survive through the ages, the use of papyrus is well documented by the hundreds of clay bullae similar to the one unveiled last year, which often preserve at the back traces of the papyrus they once sealed.

Another papyrus, which could be dated to the same period, was found in 1952 in a Judean Desert cave at Murabbaat. But such discoveries remain exceptional.

Hence the interest aroused by the mention of Jerusalem on this papyrus. Still, this is not the first time the city appears in early history. It is found, for instance, in a Hebrew inscription in a Judean cave in Khirbet Beit Lei, west of Hebron.

More importantly, it appears as early as the 14th century BCE in letters exchanged between Pharaoh Akhenaten and his vassal in Jerusalem. It might even be mentioned centuries earlier in other Egyptian texts.

The existence of a kingdom of Judah is likewise well documented as early as the ninth century, until the fall of its capital, Jerusalem, at the hands of the Babylonians around 587 BCE. From a historical and archaeological standpoint, there is no doubt that in the seventh century BCE, Jerusalem was the capital of the kingdom of Judah and bore that name.

Enter UNESCO

Why, then, did Israeli Prime Minister Benyamin Netanyahu raise a poster with a giant picture of this papyrus when it was discovered? The reason is that, on the same day, UNESCO voted on a draft resolution) on “occupied Palestine” in which the State of Israel is called “the occupying power”.

The Dome of Rock at the Temple Mount in Jerusalem. idobi, CC BY-SA

This was not the first version of this resolution, which had already caused a scandal in the northern spring. The revised version is said to be more moderate, and notably states the importance of Jerusalem “for the three monotheistic religions”. Yet, it only deals with Muslim heritage, omitting Judaism and Christianity.

Given Islamic State does not hesitate to destroy archaeological sites, UNESCO must rise above political and religious conflicts to ensure the preservation of humanity’s cultural heritage.

In Jerusalem, this heritage includes Canaanite fortifications from the second millennium BCE as much as 16th century walls erected by Ottoman Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent, the Temple of Herod the Great, and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. It’s all of this millennia-spanning heritage that UNESCO must protect, against political agendas of all sides.

Is the papyrus fake?

This background might be fatal for the authenticity of the papyrus. Finding Jerusalem mentioned in a 2,700-year-old Hebrew text on the same day UNESCO votes on a pro-Palestinian resolution is quite a coincidence.

For now, its authenticity cannot be proven, and we should be careful of independent political issues. Though we must be cautious, some make it their speciality to systematically question the authenticity of each such discovery.

It’s an easy stance to take: if the item turns out to be forged, they can boast about being the first ones who said so. If the item turns out to be authentic (but will we ever really know?), they say they were being cautious.

It is, in reality, much more difficult to risk assessing the authenticity of an item and give a truly informed opinion. A few months ago, I shared my concerns about Dead Sea Scrolls that may, in my opinion, be forgeries.

As for this papyrus, the various arguments claiming it is a forgery based on orthography are unconvincing. I have doubts about its authenticity, but on other grounds, especially the use of a margin of a sheet (a modus operandi of forgers from more than a century ago) and the alignment of the text. I believe that further analysis is required.

Still, the polemics surrounding the presentation of this papyrus could almost eclipse issues raised by its contents. Is it the king of Judah who asked that wine from his personal reserve be brought to Jerusalem? Or, did one of his subjects send him wine as a gift or as tax? Is it a neighbouring king who offered his Judahite counterpart some of his best bottles? What did the preceding lines say?

Whether this papyrus is authentic or not, it has yet to reveal all of its secrets.

![]()

En

En Fr

Fr

why’d it have to be the huffpo? i can’t mention it. 🙁

What about https://theconversation.com/how-a-2-700-year-old-piece-of-papyrus-super-charged-the-debate-over-unesco-and-jerusalem-68376

The palaeography and the skills with which the script was written, supports the authenticity of the fragment.

Moreover, how can a modern faker know to choose an Iron Age papyrus to fabricate an Iron Age document?

If modern, I will expect to find the papyrus ca 2000 years old, as such fragments are common, while Iron Age papyri are extremely rare.