My paper on the fake Dead Sea scrolls at the Museum of the Bible has been translated into English and updated.

This paper was originally published in French, but is now available in an updated English version.

You can read it on The Conversation (with better formatting) or here:

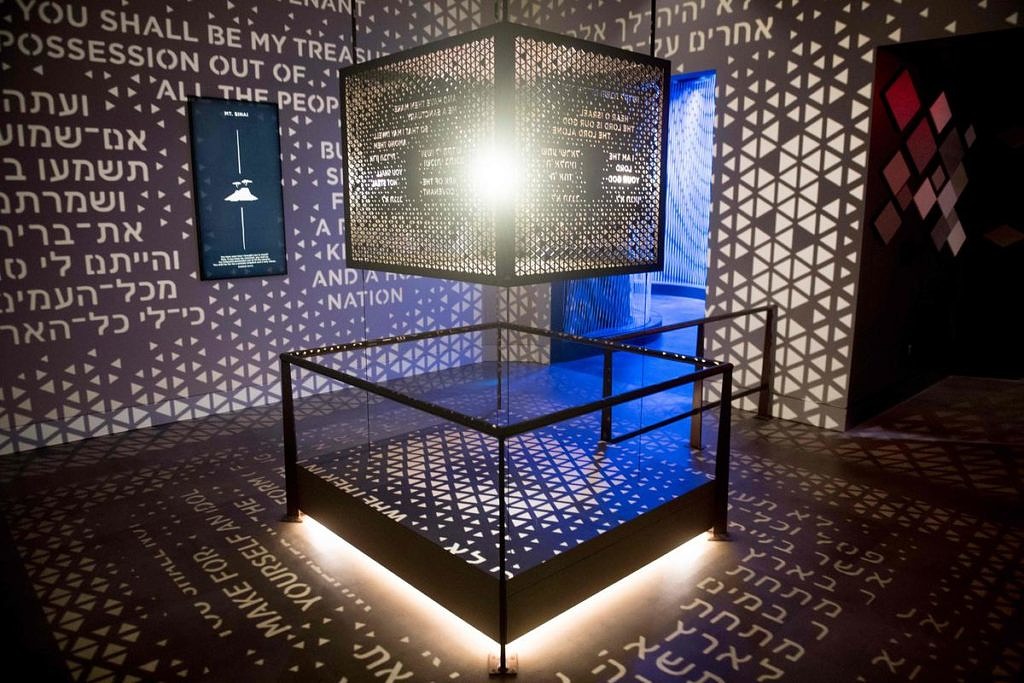

On October 22, 2018, the Museum of the Bible in Washington DC announced that five of its Dead Sea Scroll fragments were forgeries. Where did these fragments come from and what’s at stake?

The museum opened less than a year ago, on November 17, 2017, in the heart of the US capital. A 430,000-square-foot, eight-story building dedicated to the Bible and its history, it features free admission and Hollywood-style entertainment. Behind this pharaonic enterprise is billionaire Steve Green, president of the Hobby Lobby chain of arts and crafts stores. The company became widely known with the 2014 US Supreme Court case, which grew out of its refusal to comply with the contraceptive-coverage requirement of the 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, popularly known as Obamacare.

Green, a devout Evangelical Christian and grandson of a Pentecostal minister, uses his fortune to champion Christian faith and the Bible. According to him, it is the error-free word of God, the ultimate and infallible authority in matters of faith and morals. To fill his museum, Green sought to acquire some of the oldest Biblical manuscripts as evidence of the Holy Scriptures’ reliability through the millennia.

The oldest Biblical manuscripts

Green is not alone in the race: other American Evangelicals have also been trying to get their hands on ancient Biblical manuscripts to gain scholarly credibility while maintaining fundamentalist views. For example, after Azusa Pacific University acquired a number of fragments, it compared itself to the University of Chicago’s renowned Oriental Institute. The ideological and financial stakes are far from negligible.

The law of supply and demand being at work, the price of such artefacts has soared. Confetti-sized fragments of Biblical texts from the dawn of the Christian era are sold for hundreds of thousands of dollars apiece. But where do these manuscripts come from?

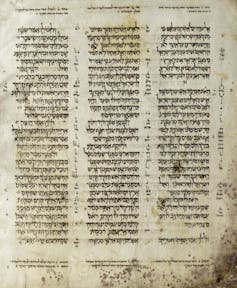

The first were discovered in 1946-47 by Bedouins searching the shores of the Dead Sea. Hidden in caves near Wadi Qumran, swaddled in cloth and sealed in jars, these scrolls resisted the centuries to convey the literary works of ancient Judaism – including the Bible. The Dead Sea Scrolls are 2,000 years old, whereas the oldest Hebrew Bible known to date is from the 10th century CE. With their discovery, we were propelled a thousand years back in time toward the origins of the Biblical texts.

An infallible Bible?

Ironically, the oldest manuscripts do not match the classical text of the Bible, including the King James translation preferred by Steve Green. The 250 Dead Sea Scrolls exhibit numerous readings, with entire chapters sometimes missing or displaced. That’s the case of a Psalms scroll in Paris’s Bible and Holy Land Museum, where Psalm 31 is immediately followed by Psalm 33, skipping Psalm 32.

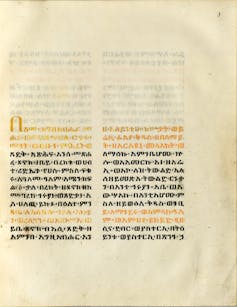

There’s more. The Qumran caves have sometimes yielded several copies of a Biblical book; not only they diverge from the classical text, but they also differ among themselves. For example, several versions of the Book of Genesis, the Psalms and Jeremiah were found, all in the same cave. One even finds books that were later rejected by Jewish and Christian authorities. Such is the case with the Book of Enoch, accepted by the Orthodox Church in Ethiopia but excluded from other Jewish and Christian Bibles.

The Bible viewed from Qumran is all but immutable and infallible. Indeed, its table of contents isn’t even finalised. Its scribes are also editors, and the text is still being woven. The discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls was a revolution for the study of the Bible, and these fragile manuscripts deserve much more than ideological, religious or political instrumentalisation – assuming they are genuine.

A fake Bible

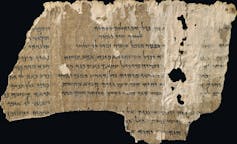

In 1947, the Bedouin showed their findings to an antiquarian from Bethlehem, Khalil Iskandar Shahin, known as Kando. He contacted potential buyers while continuing to search the area for additional scrolls. When archaeologists started excavating in 1949, it was too late: most of the caves had already been cleaned of their precious cargo. Scholars had no other choice but to negotiate with Kando, who imposed himself as the official provider of the Dead Sea Scrolls.

In 1993 a Norwegian collector, Martin Schøyen, asked Kando if he still had any scrolls for sale. “Those days are gone”, he was said to have replied. Yet a few years later, one of Kando’s sons appeared with several fragments. Thanks to the family’s reputation and quasi-monopoly, almost no doubts as to their authenticity were expressed. As a doctoral student in 2006, I expressed doubts on the authenticity of one of these fragments but was unable to examine it at the time.

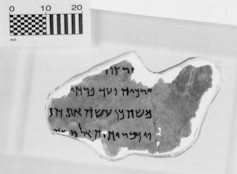

Things changed in 2012, when I joined the team working on Martin Schøyen’s Dead Sea Scrolls. I noticed inconsistencies in the surface and letter shapes, and expressed doubts to my colleagues Årstein Justnes, Torleif Elgvin and Kipp Davis. They agreed to investigate the matter and came to share my conviction. I realised that the collection of the future Museum of the Bible could also contain forgeries. While the photographs initially available on the Internet were of low quality, the clumsy script seemed the same. I asked for high-resolution pictures but my request was denied. When the official publication appeared in late 2016, I was shocked — all the fragments were fakes, copied by the same team of forgers.

I repeatedly warned my colleagues, including at a meeting in Berlin in 2017. The Museum of the Bible, soon to open, focused on damage control: its exhibition of the Dead Sea Scroll fragments was maintained, but the museum acknowledged that some scholars question their authenticity. Subsequent material analysis led the museum to announce the withdrawal of five fragments. Does it mean that the museum’s other fragments are genuine? No. They have simply not been subjected to the same tests. I am still of the opinion that the 13 published Dead Sea Scroll fragments are forgeries, so the story is not over.

What about other Evangelical collections in the US? More than a year ago, I warned Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary that their fragments may be fake; I requested photographs but was denied. Hopefully, the Museum of the Bible’s recent decision will set an example and prompt other private collectors to act. Stay tuned for the next episode!

Losing sight of the Bible itself

The Museum of the Bible and other American evangelical institutions claim they have secured some of the oldest biblical manuscripts. In so doing they hope to gain scholarly credibility but, ironically, the opposite has happened. In 2017 the Museum of the Bible was also convicted of illegally importing thousands of Iraqi artefacts and ordered to pay a $3 million fine. Between the instrumentalisation of religious history, buying forgeries, and aiding and abetting smuggling, these defenders of the Bible seem to have forgotten a well-known verse: “Ill-gotten gains never profit” (Proverbs 10:2).![]()

En

En Fr

Fr